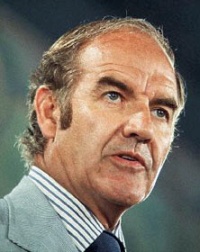

I became a lifelong political convention junkie in 1972, the year that George McGovern secured the nomination with a brilliantly executed ploy that nobody saw coming until it was over, and that even the sainted Walter Cronkite mistakenly reported as a disaster.

I became a lifelong political convention junkie in 1972, the year that George McGovern secured the nomination with a brilliantly executed ploy that nobody saw coming until it was over, and that even the sainted Walter Cronkite mistakenly reported as a disaster.

I was 18 years old. Most of the Democratic convention was held in the wee hours of the morning, and I went sleepless following the battle on black and white TV, jumping up every few minutes to twirl the dial to another network. All realtime analysis came from the anchormen, and at the crucial moment, the anchormen had no idea what was happening.

After a tumultuous primary season, McGovern had eked out a bare delegate majority by winning California’s winner-take-all primary with 44% of the vote. But his opponents had challenged the winner-take-all rule and won a victory in the Credentials Committee, which reallocated 56% of California’s delegates to McGovern’s opponents. To win the nomination, McGovern had to overturn that decision via a vote on the convention floor.

Could McGovern win that vote? Everyone thought so, until they thought otherwise. There was another credentials challenge before California—South Carolina, with nine delegates at stake. Presumably the South Carolina vote would reveal McGovern’s true strength and predict the California outcome.

Along with the rest of the country, I gasped as the roll call proceeded and it became clear that McGovern was losing the fight over South Carolina. Cronkite and the other network anchors announced in solemn tones that McGovern had lost control of the convention, that he would surely lose the fight over California, and that the nomination would soon be up for grabs.

Meanwhile, behind the scenes, McGovern’s aides were celebrating the South Carolina loss that they themselves had orchestrated. They and a few of their counterparts in rival campaigns were the only people in America who understood what had just happened.

********************************************

Come back with me to 1972. As the drama is unfolding, here’s what the politicians realize and the news anchors don’t: Because the disputed delegates can’t vote on their own credentials, there is some ambiguity about how many votes McGovern needs to win those credentials fights. Does he need a majority of all the delegates (including the non-voting Califorians and South Carolinians) or just a majority of the voting delegates? Does he need 1509 votes, or just 1433?

To McGovern’s great relief, the party chairman has ruled that 1433 is enough.

But McGovern still faces a potential nightmare scenario: Suppose he wins the South Carolina fight with more than 1433 votes but less than 1509. Then, this result is sure to be challenged from the floor, triggering a fight over the rules. Because this is a rules fight, as opposed to a credentials fight, the disputed delegates will be allowed to vote, which means McGovern will probably lose. The 1433 rule will be overturned and the 1509 rule will take its place. Next it’s on to the fight over California, and McGovern will have an impossibly high hurdle to clear. He’ll lose the California credentials fight, and his campaign will be over.

Of course the rules fight is sure to come up sooner or later, but if it can be delayed until the California credentials fight is on the table, then the hostile Californians will be barred from voting. Then McGovern wins the rules fight, which means he wins the credentials fight, which means he wins the nomination.

So while McGovern would love to win the South Carolina fight with more than 1509 votes, his second choice is to lose with fewer than 1433, delaying the rules fight. As the South Carolina vote unfolds, delegates on the floor receive constantly updated instructions by walkie-talkie from the candidates’ trailers. McGovern’s opponents—Hubert Humphrey, Ed Muskie, and others—try desperately to engineer an outcome between 1433 and 1509. McGovern, realizing that 1509 is probably out of reach, aims for less than 1433.

In the end, the McGovern position commands 1429 votes. Scores of McGovern delegates have followed instructions to vote against the South Carolina challengers and against their own instincts. This is all the more remarkable because the South Carolina challengers are seen as feminist standard-bearers and command a lot of sympathy in the McGovern ranks. In other words, McGovern, who is being described on every network as an ineffectual loser, has in fact won a great victory through iron discipline.

*************************************

As the candidate breathed a sigh of relief, all of America—at least those of us who were watching at 2AM—believed his campaign was over. Once it came clear what happened, I was hooked on political minutiae for life. Every year, I hope for something as exciting as 1972. I’m not optimistic that this will be the year, but I’ll be watching just in case.